|

Casa

Mesquita, Colva, Goa

First Impressions

Casa Mesquita is all it's cracked up to be

in The Rough Guide. Huge, dark, cool, neglected and full of atmosphere.

I appear to be the only guest. A woman named Maria in a turquoise sari

shows me around and brings me rose-flavoured tea, which I drink in my room

beside the open window gazing at banana plants and savouring the exotic

birdsong. I have a rickety four poster bed in which I cannot wait to sleep. |

|

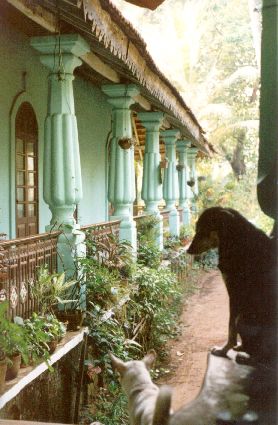

Two dogs sprawl on

the verandah outside, a black and tan named Khir and a white, Branco. The

house is in the old Portuguese colonial style, built in the 1930's by the

father of the present owner, Alberto Mesquita. "In the colonial days,"

Alberto informs me, you could get anything from anywhere in the world."

The hexagonal red, cream and black floor

tiles were imported from Italy. The place is astonishing; everywhere I

look I find more detail. Intricate mosaics bedeck the long verandahs. The

ice-cream pink hallway has plaster hands sprouting from the wall to hold

the curtain rails. The long net curtains hanging over the the internal

doors and the Long Room's french windows have a pattern which echo the

design of the arched stained-glass fanlights.The high arched windows inside

the house have shutters, as do the doors: they are not doors but four hinged

panels which open at the centre, fastened by crude iron hooks. I want to

take everything home with me in photographs but the cool shade will keep

Casa Mesquita's secrets unphotographable. |

|

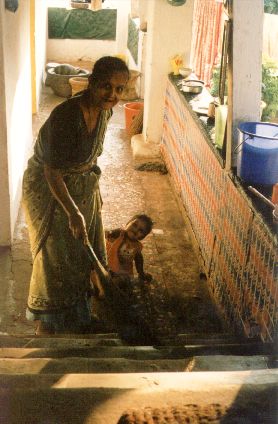

Maria, the housekeeper

has a grandson, Bernardo, who runs naked and alone through the empty echoing

house all day. His only playmates are the two dogs who bear his fierce

bearhugs stoically.

It is Bernardo's second birthday on the day

I arrive. We eat with Alberto, Maria, the birthday boy and his mother that

evening, a celebratory meal of Goan home cooking: chicken xacuti, sag paneer,

salad and fried rice.

|

|

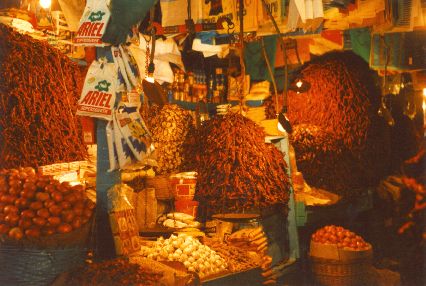

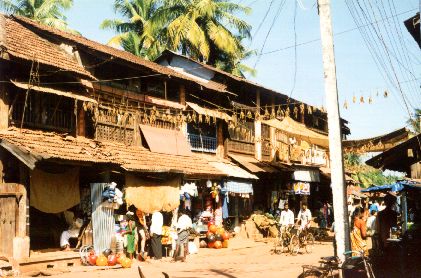

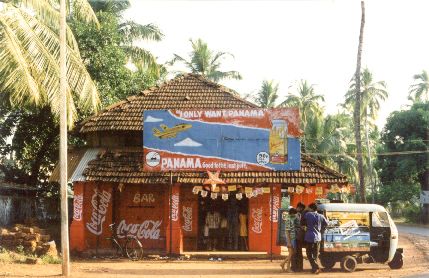

Corner shop, Colva

crossroads.

The star-shaped lampshade hanging above

the door is a Christmas decoration. Almost every house in Goa has at least

one of these at Chirstmastime, lit at night. Larger houses may have three

or four along the verandahs. Travelling at night by tuk-tuk or taxi, the

effect is a myriad of stars twinkling between the palm trees. |

|

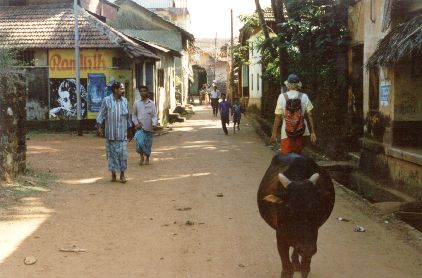

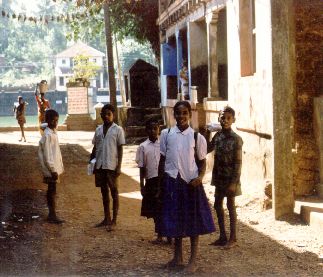

The people all stare.

Wherever one walks, the children and adults

alike call "Namaste!" and down a side street a schoolgirl with bare feet

holds out her hand for me to shake: "Namaste, hello! My name Sangheeta.

Where you from? What is your name?" She introduces her companions, the

questions are repeated, then she thanks me, shakes my hand again, and they

continue on their way to school. |

|

I have a room in a guest-house

only yards from the sea, a small bare white-washed cell with an earth floor

and a rough wooden door. My bed is two thin lumpy mattresses on a wooden

bench.

The view from the guest-house is beautiful.

A flight of tiny red brick steps that weave up the steep face of the headland:

the way to Kudle beach, and further on, Om beach. Other guests tell me

about the beauty of these beaches, no more than an hour ot two's walk away. |

|

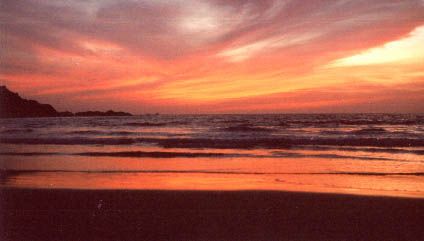

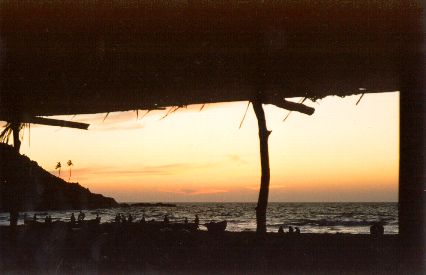

Near sunset, the fishing boats

draw in, and pariah kites swoop down to the sand to catch the tiny silver

fish that fall from the nets.

I swim at midnight in the dark velvet sea.

Phosphoresence glitters like green sparks. The only light I can see is

that of the temple on the hill, high up and twinkling like a star. |

|

At the top of the headland a spectacular

view spreads out below. The golden strand of Gokarna beach runs endlessy

into the distance. Far on the horizon behind layer upon layer of forest-covered

hills the Western Ghat mountains reach to the sky. |

|

Nestled in the protective lee of steep headlands,

Om Beach is exceptionally beautiful. Two perfectly curved crescents of

beach allow the sea to gently lap at the shore, and at their conjunction

a long arm of rock stretches out into the water, to form the shape of the

spiritual Indian Om symbol. |

|

The shrine on Gokarna's headland. |